Long COVID and Disability

The global COVID-19 pandemic is not yet over.

We have been living in this pandemic for over 2 years, with over 551 million confirmed cases of COVID-19, sadly including over 6 million deaths, reported by the World Health Organization. Much progress has been made with strategies to reduce transmission, vaccinations, and treatments for acute COVID-19. Hospitalisations and death are important outcomes to understand, but they are not the only outcomes of importance. Not everybody fully recovers from COVID-19, with disability affecting more and more people with Long COVID.

It has been estimated that more than 144 million people are living with Long COVID around the world, affecting approximately 1 in 5 people aged >18 years in the United States (US) following COVID-19 illness, and 3.1% of the general population of the United Kingdom (UK). In the UK, 1.4 million people experience limitations in daily activities after COVID-19, meaning a majority (71%) of people experience disability after COVID-19.

The increasing global scale of Long COVID with many human and economic impacts, adds to disability being an extremely important health issue to think about, address, and research. So what is disability? Is rehabilitation what people with Long COVID need?

Due to the historical harms imposed upon people with energy limiting conditions such as ME/CFS, through inappropriate rehabilitation approaches such as graded exercise therapy (GET) and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), rehabilitation can sometimes be seen by people as a ‘dirty’ word. In this blog, let’s explore some of the history and understanding of disability. In the next blog, we will explore rehabilitation.

Disability

The conceptualisation of disability is complex and has evolved over time. Initially, disability was viewed within the medical model as a phenomenon determined by impairments of body structure or function. This remains a common approach to thinking about disability, in which disability is viewed as a problem that exists in a person’s body. This model implies that the person with functional limitations (impairments) requires treatment or care to fix the disability and does not consider contributing environmental and social factors. This medical model has been perceived as ‘outdated and oppressive’.

Understanding of disability then shifted towards the social model that framed disability as resulting from barriers imposed by societies (e.g. inaccessible built environments, information communication) that isolate and exclude people with impairments from full and equal participation. The social model emphasised that exclusion is the real problem, caused by a social failure to make proper inclusive arrangements rather than by individual biological dysfunctions. The social model has been criticised for creating a dichotomy between impairments and disability, which may exclude dimensions of lives of people with disability, such as impairments.

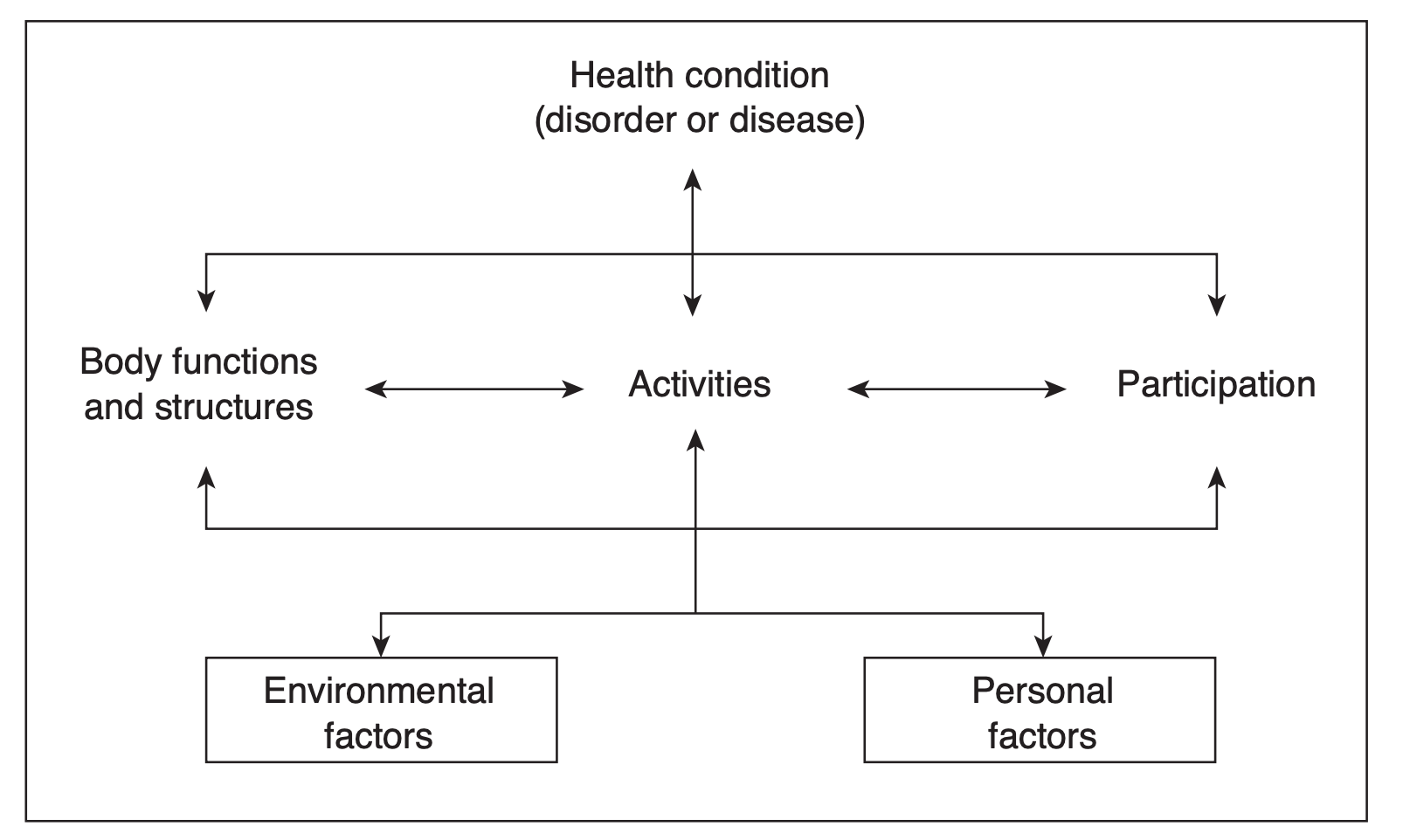

The subsequent predominating framework of disability, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), combines elements of both medical and social models leading to a ‘bio-psychosocial’ framework. The ICF describes functioning and disability as multidimensional and the outcome of interactions between a person’s health condition(s) and context (environmental and personal factors), involving one or more dysfunctions at the level of impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions. An impairment is a problem in body function of structure. An activity limitation is a difficulty encountered by an individual in executing a task or action. A participation restriction is a problem experienced by an individual in involvement in life situations. The purpose of the ICF is to provide a globally agreed, common language and framework for describing functional status in order to allow for comparisons. The ICF is not specific to any health condition, and may not accurately capture the complexity of some health conditions, the day-to-day health-related consequences, and their significance from the perspective of people living with conditions such as HIV. Additionally, the ‘bio-psychosocial’ framework has changed how disability is approached for some health conditions, such as ME/CFS.

The Episodic Disability Framework presents a new way to conceptualise disability based on the experience of people living with HIV. The Episodic Disability Framework conceptualises disability as multidimensional and episodic, characterised by unpredictable periods of wellness and illness. Dimensions of disability include any of the following:

1. physical symptoms and impairments

2. cognitive symptoms and impairments

3. mental or emotional symptoms and impairments

4. difficulties with day-to-day activities

5. challenges to social inclusion

6. uncertainty or worry about the future.

Similar to the ICF, the Episodic Disability Framework highlights how environmental and personal factors including extrinsic factors (e.g. level of social support and stigma) and intrinsic factors (e.g. living strategies, age, and personal attributes) may exacerbate or alleviate each dimension of disability. The Episodic Disability Framework describes the health-related consequences, adverse effects of treatments, and concurrent health conditions, which may fluctuate over time. The novel contributions of the Episodic Disability Framework are identifying ‘uncertainty’ or worrying about the future as a key dimension of disability, plus the episodic nature of disability over time. The Episodic Disability Framework has been conceptualised within the experiences of disability living with Long COVID, is being researched to better understand Long COVID disability experiences, and develop an appropriate measurement tool to measure the presence, severity and episodic nature of disability experienced by people living with Long COVID. The Long COVID Video Series also explores episodic nature of Long COVID in a short video.

Defining disability is complex, with a range of available definitions, frameworks and conceptualisations. Disability can however be broadly defined as any physical, cognitive, mental or emotional, and social health challenges that can be experienced as episodic in nature with periods of fluctuating health. Understanding a history of disability allows us to appreciate that disability has been defined as multidimensional, episodic, and the outcome of a person’s body, environment, and society. It is distinct but related to other concepts such as health and quality of life. Fundamentally, disability is a universal human experience, where everybody can be placed on a continuum of functioning from no disability (full functioning) to complete disability, and, either currently experiencing, or vulnerable to experiencing, disability over the course of life.

This blog has been written and adapted from a publication written by the author.