Exercise

This episode is from the Long COVID Video Series. Please visit the website to access audio and written versions and translations.

Exercise is different to physical activity. Exercise is planned, structured, repetitive and intentional movement intended to improve or maintain physical fitness. Physical activity is any bodily movement produced by muscles that results in energy expenditure. Physical fitness is a set of attributes that are either health- or skill-related. Exercise and physical activity are often recommended as public health and rehabilitation interventions to prevent, manage or improve diseases, health related challenges, disability, quality of life and well-being.

The World Health Organization rehabilitation guidelines for adults living with Long COVID, are clear that exercise interventions should not be used in people experiencing post-exertional symptom exacerbation.

An editorial in the Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy (JOSPT) discusses safety considerations with physical activity and exercise with Long COVID. World Physiotherapy published briefing paper 9 on safe rehabilitation approaches for people living with Long COVID specific to physical activity, including exercise and sport. This briefing paper was led, managed and executed by Long COVID Physio. The World Health Organization living guideline for the clinical management of COVID-19, section 24, focuses on Long COVID rehabilitation and provides explicit guidance on when exercise is not safe of effective.

World Physiotherapy provided a range of useful resources for #WorldPTDay 20201 available in in nearly 60 different languages in their toolkit. Much of this information was based on the World Physiotherapy briefing paper and reflects growing numbers of resources about Long COVID rehabilitation. The information provided includes an activity diary and information sheets on:

The National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) cautions against using graded exercise therapy for people recovering from COVID-19. Graded exercise therapy (GET) is a structured exercise programme that increases the amount of physical exertion a person performs over time. The National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) removed graded exercise therapy from the updated ME/CFS guideline. The Workwell Foundation opposes GET in ME/CFS.

People living with Long COVID can experience fatigue and post-exertional symptom exacerbation (PESE), with post-exertional symptom exacerbation negatively impacting on ability to function in day-to-day life and work. Persistent exertional intolerance has been associated with impaired systemic oxygen extraction (eg: how oxygen gets to the muscles) and ventilatory inefficiency (eg: abnormal breathing responses to exercise).

Exercise intolerance in people living with Long COVID is not only caused by deconditioning. A narrative review of 32 Cardiopulmonary Exercise Test (CPET) studies does not support deconditioning as a primary mechanism, with Long COVID sequelae being multifaceted and requiring individual diagnosis and treatment.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 38 studies which performed CPET on 2160 individuals 3 to 18 months after SARS-CoV-2 infection, including 1228 with symptoms consistent with Long COVID, identifies that exercise capacity is reduced in people with Long COVIF compared to people who recovered or have no symptoms. Deconditioning may be more common among those hospitalised with other patterns (peripheral, ventilatory inefficiency) predominant among non-hospitalized patients. On results of noninvasive CPET, peripheral mechanisms related to oxygen delivery and/or extraction due to muscular, mitochondrial, or vascular pathology can be misattributed to deconditioning. Other mechanism for reduced exercise capacity include (a) dysfunctional breathing or hyperventilation, (b) chronotropic incompetence, (c) preload failure despite normal resting cardiac function, (d) autonomic dysfunction, (e) endothelial dysfunction and (f) impaired peripheral oxygen extraction. Overall, this research found consistent evidence that deconditioning is not the only explanation of reduced exercise capacity in Long COVID, especially among individuals who were not hospitalized.

There are marked differences in heart rate responses to exercise in people with Long COVID, altered gas exchange (low end tidal CO2) including over the long term, circulatory impairment, endothelial dysfunction, and reduced aerobic capacity. People with Long COVID have neuroimmune and neuro-oxidative origins to their symptoms such as fatigue. Elite athletes with reduced athletic performance after COVID-19 have reduced anaerobic thresholds demonstrated on CPET, meaning there is a virally mediated mitochondrial dysfunction beyond normal ‘deconditioning’, associated with impaired fat oxidation. Skeletal muscle biopsies demonstrate people with long COVID have immune-mediated structural changes of the microvasculature, with fewer capillaries, thicker capillary basement membranes and increased numbers of CD169+ macrophages, which may help better understand exercise intolerance, fatigue and pain experienced by people living with Long COVID.

Chronic fatigue associated with Long COVID is comparable with transient fatigue caused by high-intensity exercise, in terms of vascular effects. However, an obvious difference is that fatigue caused by high-intensity exercise is fully reversible after 1–3 hours of rest, unlike Long COVID fatigue. Furthermore, impaired exercise capacity has been linked to microvascular or endothelial dysfunction, with elevated biological markers of clotting, VWF(Ag):ADAMTS13 ratio, resulting in 4 times more likely impaired exercise capacity. We do not yet fully understand exertional intolerance, but recognise the impact this has on health and functioning.

As such, caution with exercise has been recommended in Physiotherapy guidelines, and exercise is not a safe rehabilitation intervention to treat fatigue among people experiencing post-exertional symptom exacerbation. This is because physical exertion is a common trigger for symptom exacerbation and relapse among people with Long COVID. Among a sample of 477 people living with Long COVID, 74.84% reported physical activity made symptoms worse. Which is why pacing is recommended, yet many healthcare professionals still promote graded exercise therapy, meaning people with Long COVID are potentially receiving harmful recommendations from healthcare professionals about how to be physically active. This may also represent a misunderstanding of pacing.

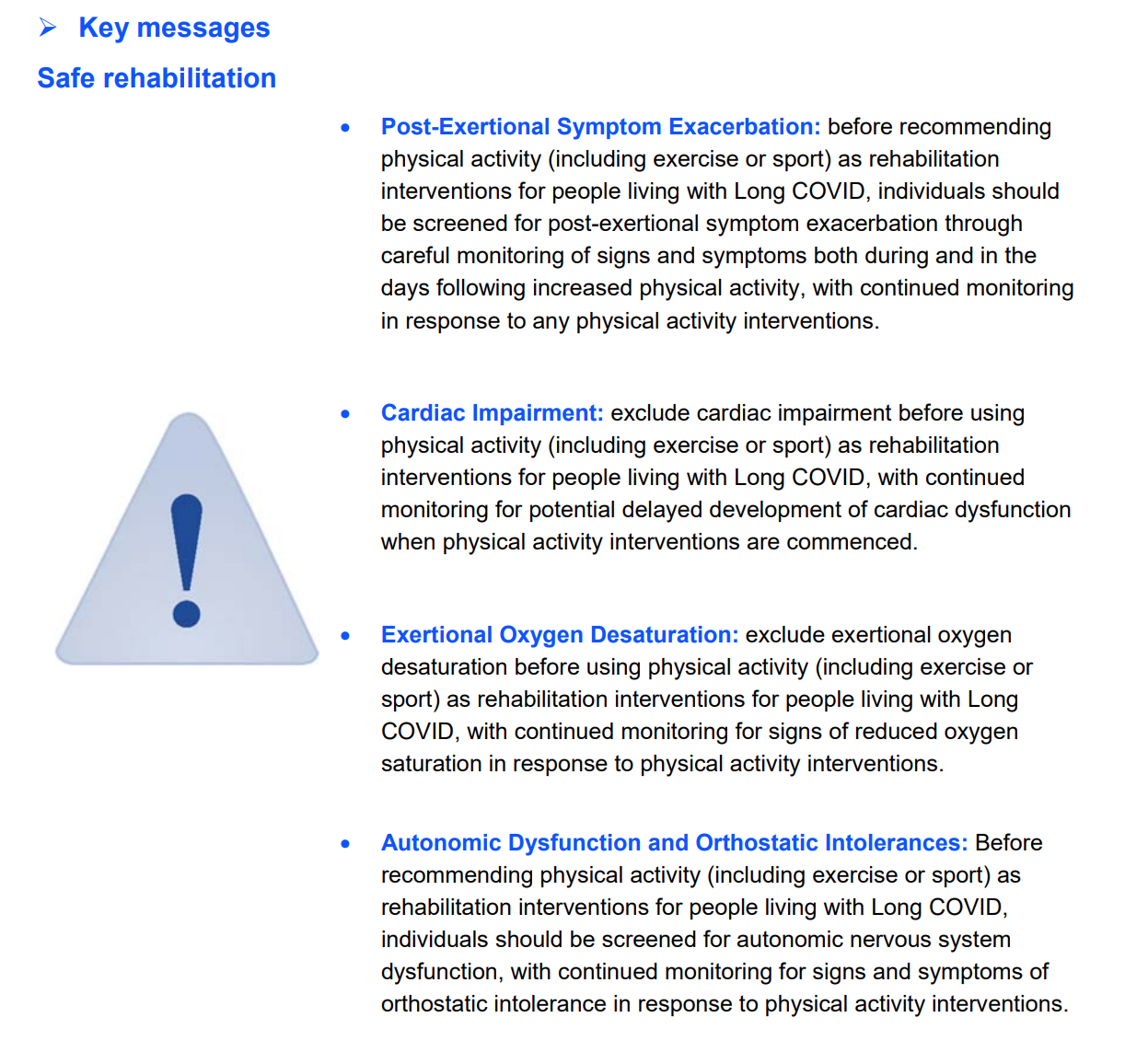

Appropriate risk stratification should be performed to assess and continually monitor for post-exertional symptom exacerbation, before exercise can be considered as a rehabilitation intervention. The DePaul Symptom Questionnaire might be a suitable tool to assess post-exertional symptom exacerbation among people living with Long COVID.

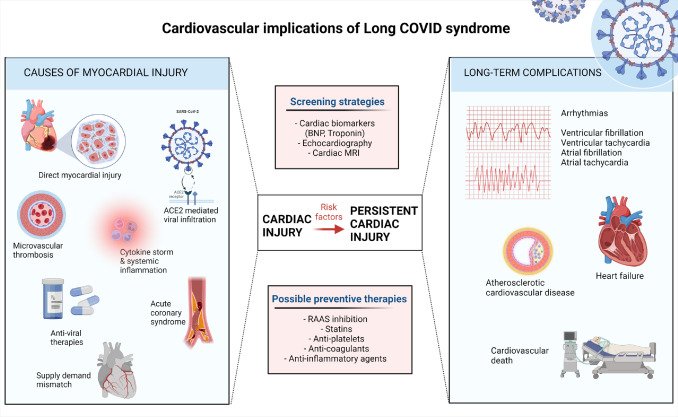

People living with Long COVID can have body organ impairments, including the heart, lungs, kidneys, liver, pancreas and spleen. When examined with cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR), one in five people with Long COVID have cardiac abnormalities 1 year after after infection, including left ventricular or right ventricular dysfunction and dilatation and/or abnormal T1mapping. Cardiac MR has been suggested to improve diagnostic accuracy characterising ischemic and non-ischemic injury and unraveling subclinical cardiomyopathies. Larger than expected burden of myocardial injury is demonstrated among people with Long COVID managed in the community for initial COVID-19 infection, and persistent cardiac injury is an important component of Long COVID. Screening for potential cardiac involvement has been recommended for athletes recovering from COVID-19. Appropriate risk stratification should be performed to asses and continually monitor for potential cardiac symptoms and impairments, before exercise can be considered as a rehabilitation intervention.

People living with Long COVID can experience a decrease in pulse oxygen saturation (desaturation) on minimal exertion. A fall of 3% in the saturation reading on mild exertion is abnormal and requires investigation. Appropriate risk stratification should be performed to assess and continually monitor for potential desaturation on exertion, before exercise can be considered as a rehabilitation intervention. Pulse oximetry should be used to monitor levels of oxygen in the blood, to alert if oxygen levels drop below safe levels.

Exercise is currently a topic of debate within the emerging field of Long COVID rehabilitation. Long COVID Physio advocates for extreme caution with exercise and appropriate risk stratification, to exclude post-exertional symptom exacerbation, potential cardiac involvement, exertional destauration, and orthostatic intolerance, before commencing exercise as a rehabilitation intervention. More research is needed to identify if and when exercise is safe or effective for children, young people, and adults living with Long COVID. Exercise and physical activity may be beneficial for some people recovering from acute COVID-19 and living with Long COVID, but we must do no harm. Therefore caution is advisable, until research is available to guide best practice, on when and for who exercise and physical activity is safer.

Current and future research should learn from the experiences of ME/CFS and other infection triggered illnesses, in the design, implementation and reporting of studies.

This video by Workwell Foundation and Action CIND, explore 20 years of research in ME/CFS to answer why “working out doesn’t work out”.

Many of our podcasts discuss the topic of caution with exercise from personal, clinical and academic perspectives.

Date Last Revised: 24th July 2024